Sediment Cores: What, How & Why

What is a sediment core?

A sediment core is a tube of mud extracted from the bottom of a river, lake or ocean. Other types of cores include: ice cores, rock cores, and peat cores, to name a few. Some types of cores, tree-ring cores and coral cores, reveal growth patterns over hundreds to thousands of years.

In general, coring gives scientists access to layers of material that have been accumulating over long periods of time and what they find in these layers can give valuable insights into Earth’s climate history.

How do we collect sediment cores?

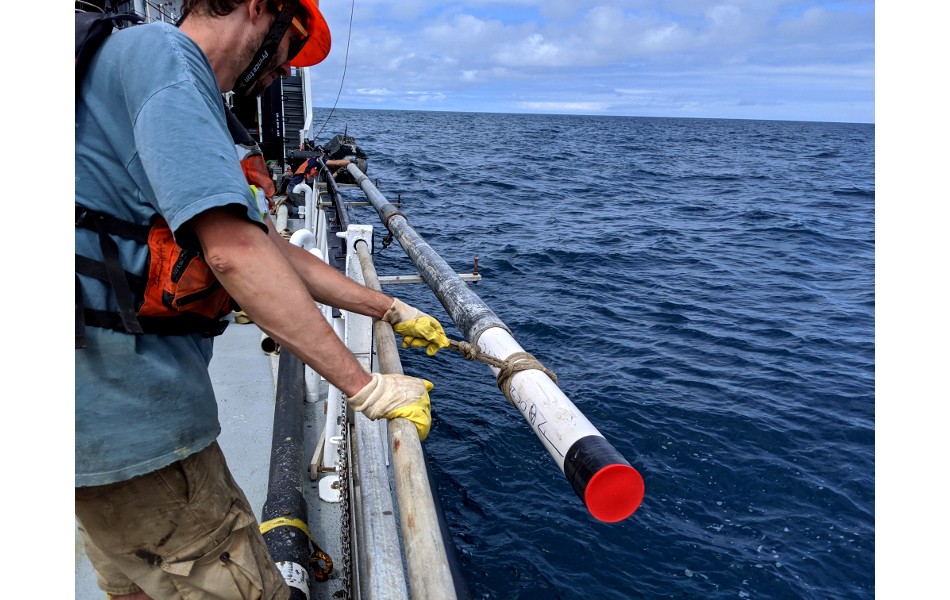

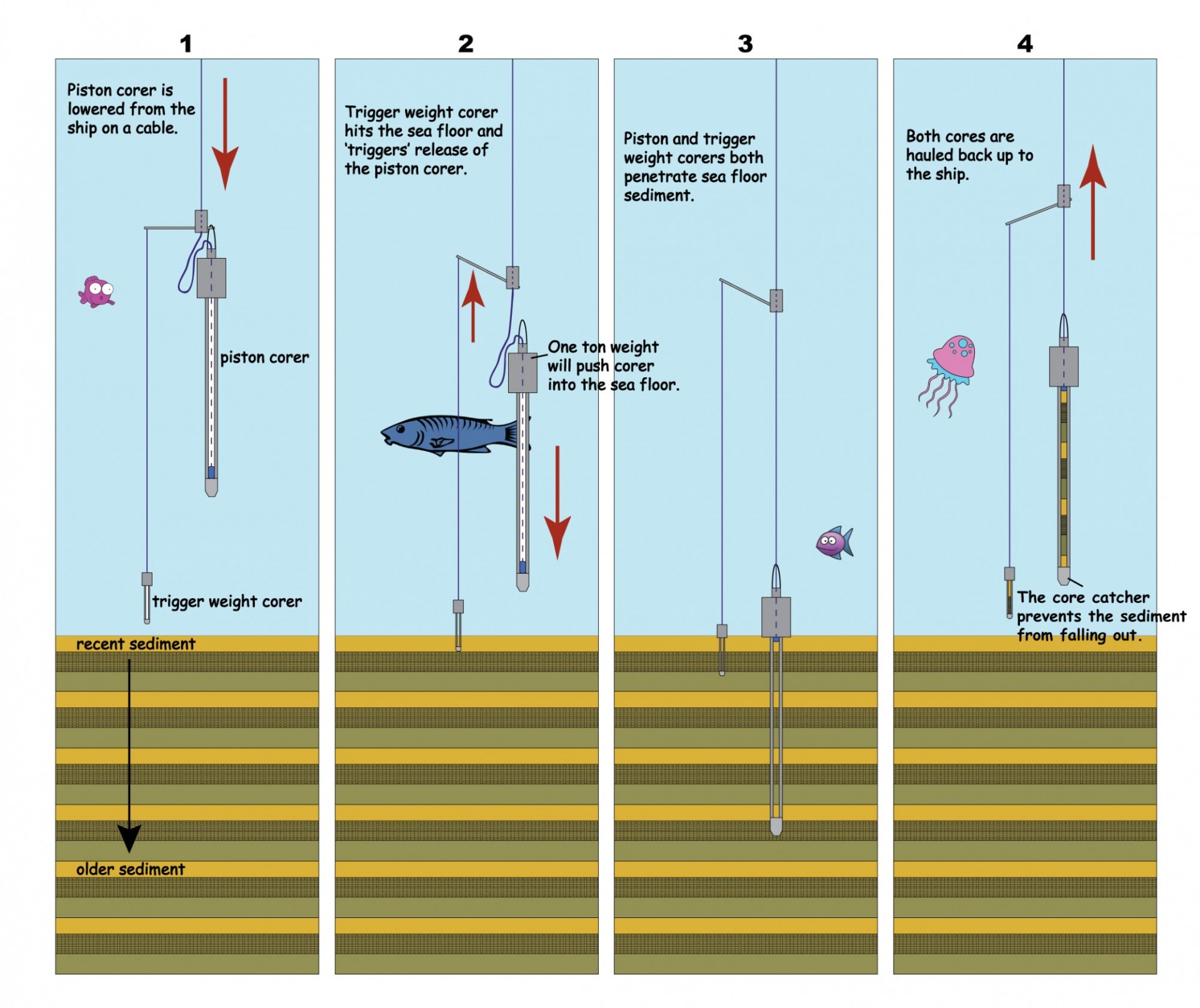

The collection at the LDCR is predominantly marine sediment cores collected using a Piston Corer. A Piston Corer is a long empty steel pipe (the coring barrel) with weights on top, a piston mechanism inside the coring barrel and a 'core catcher' in the bottom. It is lowered from a ship and allowed to free-fall into soft sediments, the weights on top driving the barrel into the mud. The core catcher in the bottom is a type of one-way valve that allows sediments into the coring barrel. After the Piston Corer penetrates the sediments, the piston is slowly pulled up inside the coring barrel, creating a weak vacuum and pulling in more sediment. In many instances, Piston Cores over-penetrate the sediments they are coring, losing the uppermost layers. To capture the uppermost sediments, a Trigger-Weight Core is taken alongside a Piston Core.

Once the core is pulled up to the ship, the pipe containing the sediments is pushed out of the coring barrel and cut into manageable sections. Each section is then cut in half, lengthwise, to allow access to the sediments within. For more information on piston and other types of coring click here.

The image below illustrates how a piston corer works (click on the image to enlarge).

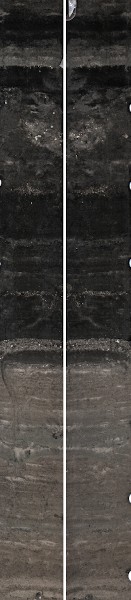

Below are two images of the same core taken in the Long Island Sound. The researchers used clear PVC so you can see the sediments within the tube before it is cut open (left image). The image on the right is the same core after it was split open showing all of the layers in detail!

Why do we collect sediment cores?

Sediments are laid down in layers so the oldest layers are at the bottom and recent layers are on top. These layers hold records of Earth's history that are revealed in sediment cores. One of the reasons scientists study sediment cores is to gain insights into how Earth's climate has changed over time. The sediments in marine cores can be as much as 140 million years old and contain many things that help scientists investigate past local and global changes.

Plankton "Shells"

Trillions of individual plankton live in the oceans and, when they die, their remains fall to the ocean floor. The different types of plankton that are found in sediment cores (foraminifera, diatoms, radiolaria, coccoliths...) build "shells" that are preserved in the sediments and can tell us many things about Earth's climate when the organisms were alive.

Click through the slideshow, to learn more about the biogenic component of sediment cores!

[Click on each image for information.]

Image Carousel with 6 slides

A carousel is a rotating set of images. Use the previous and next buttons to change the displayed slide

-

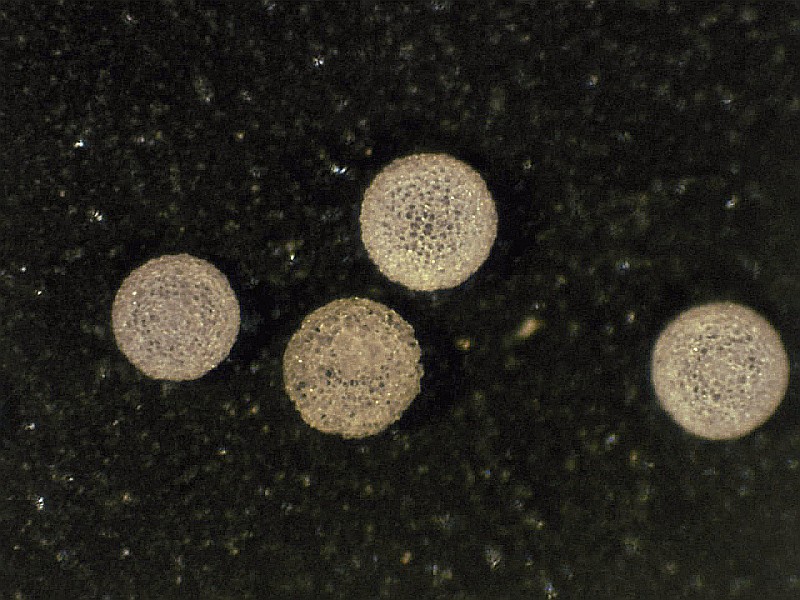

Slide 1: Mixed plankton shells (microfossils). The shells of a variety of different types of plankton: these are the ones most often used by scientists due to their natural abundance and larger size which makes them easier to work with.

-

Slide 2: Foraminifera. "Forams" first appeared in the world oceans 500 million years ago and have shells made from calcium carbonate. Changes in species assemblages throughout a sediment core give us clues to what conditions were like when the organisms were alive.

-

Slide 3: To build their shells, forams use chemical elements found in the seawater around them. Some of these elements - stable isotopes of Oxygen and Carbon and concentrations of Magnesium, Lithium and Carbon - give us valuable insights into Earth's paleoclimate.

-

Slide 4: Diatoms. Diatoms are a type of algae and their shells are made from silica. Diatoms can be used as a proxy for nutrient availability (more nutrients means more diatoms) which, in turn, can tell us about precipitation, upwellings, wind strength, and erosion.

-

Slide 5: Radiolaria. Radiolarians create opaline-silica shells. Radiolaria species are very sensitive to water temperatures and their relative abundances tell scientists how ocean temperatures and circulation patterns have changed through time.

-

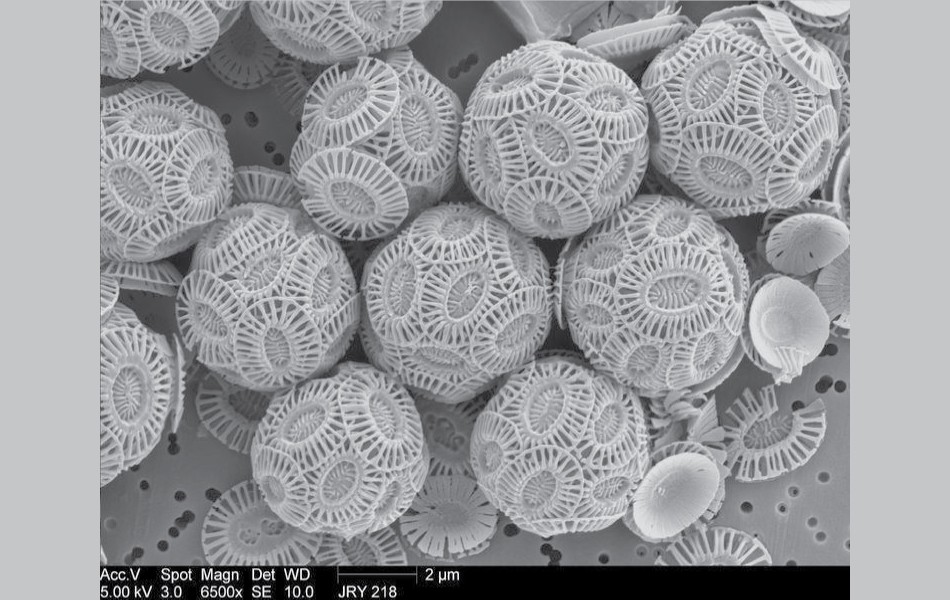

Slide 6: Coccolithophores. Coccoliths are another type of algae but make their shells from calcium carbonate. They are considered “nanno-fossils” because of their extremely tiny size (about 35 microns on average!). Since Coccoliths are an algae (like Diatoms) and make calcium carbonate shells (like Forams), they can provide similar information as these other groups.

Mixed plankton shells (microfossils). The shells of a variety of different types of plankton: these are the ones most often used by scientists due to their natural abundance and larger size which makes them easier to work with.

Foraminifera. "Forams" first appeared in the world oceans 500 million years ago and have shells made from calcium carbonate. Changes in species assemblages throughout a sediment core give us clues to what conditions were like when the organisms were alive.

To build their shells, forams use chemical elements found in the seawater around them. Some of these elements - stable isotopes of Oxygen and Carbon and concentrations of Magnesium, Lithium and Carbon - give us valuable insights into Earth's paleoclimate.

Diatoms. Diatoms are a type of algae and their shells are made from silica. Diatoms can be used as a proxy for nutrient availability (more nutrients means more diatoms) which, in turn, can tell us about precipitation, upwellings, wind strength, and erosion.

Radiolaria. Radiolarians create opaline-silica shells. Radiolaria species are very sensitive to water temperatures and their relative abundances tell scientists how ocean temperatures and circulation patterns have changed through time.

Coccolithophores. Coccoliths are another type of algae but make their shells from calcium carbonate. They are considered “nanno-fossils” because of their extremely tiny size (about 35 microns on average!). Since Coccoliths are an algae (like Diatoms) and make calcium carbonate shells (like Forams), they can provide similar information as these other groups.

Terrigenous Material

These are particles that come from on land. Very small particles can get blown far out to sea by strong winds but larger grains need more energy to carry them and are most commonly deposited into the oceans via rivers, streams, and run-off after storms where they collect on the continental margins (within a few hundred miles of the coast). These larger particles are typically mineral grains that were eroded from rock formations.

Both the type and size of different mineral grains can tell scientists about changes in weathering and erosion patterns, ocean currents, earthquake histories, and even how far icebergs have traveled!

This slideshow talks about just a few ways these components of sediment cores are used by scientists.

Image Carousel with 3 slides

A carousel is a rotating set of images. Use the previous and next buttons to change the displayed slide

-

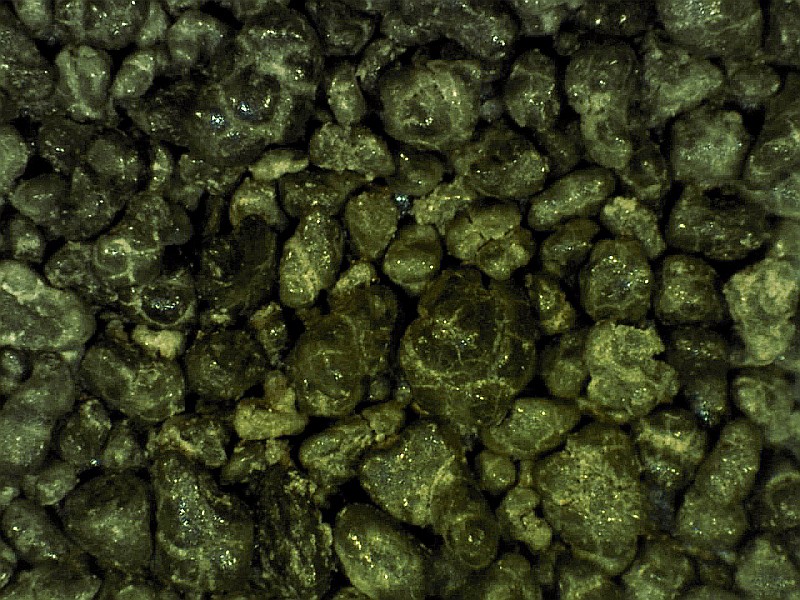

Slide 1: Well rounded (smoothed) mineral grains. The degree to which the grains are rounded can tell us how far they have been transported: the more rounded they are, the further they have traveled.

-

Slide 2: Ice-rafted debris. As glaciers move across land they scrape up bits of dirt and rock. When parts of the glacier break off and become icebergs they carry this debris out to sea. As the iceberg melts, the debris it was carrying drops to the ocean floor.

-

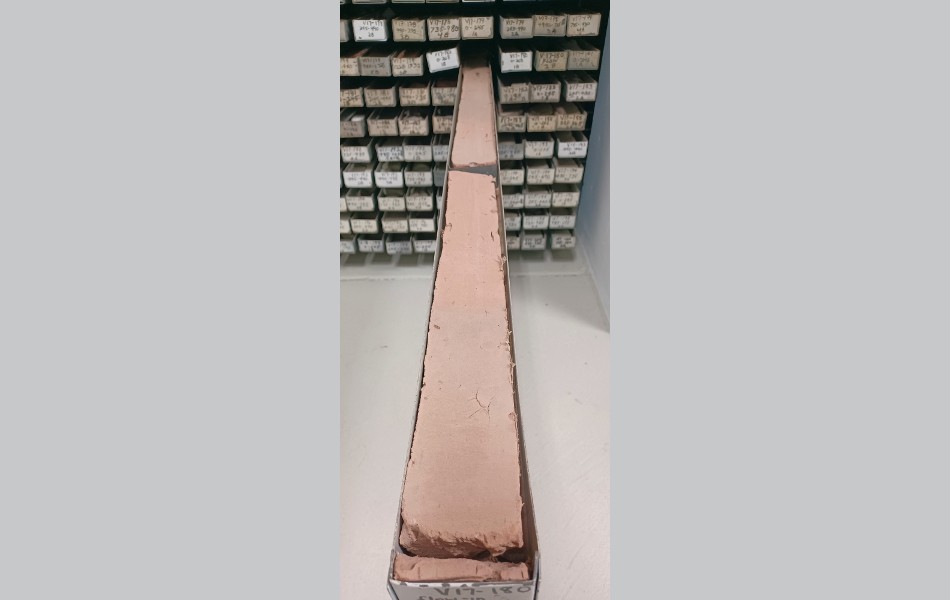

Slide 3: Deep Sea Clays. The sediments of the Abyssal Plain (the deepest parts of the ocean floor (aside from the trenches)) are mostly made of clay grains that were blown off land (Aeolian).

Well rounded (smoothed) mineral grains. The degree to which the grains are rounded can tell us how far they have been transported: the more rounded they are, the further they have traveled.

Ice-rafted debris. As glaciers move across land they scrape up bits of dirt and rock. When parts of the glacier break off and become icebergs they carry this debris out to sea. As the iceberg melts, the debris it was carrying drops to the ocean floor.

Deep Sea Clays. The sediments of the Abyssal Plain (the deepest parts of the ocean floor (aside from the trenches)) are mostly made of clay grains that were blown off land (Aeolian).

Authigenic Minerals

These are minerals that form “in place”. They require specific conditions to grow and, therefore, can tell scientists a lot about how an area has evolved over time.

Click through this slideshow to learn about a few of these minerals.

Image Carousel with 5 slides

A carousel is a rotating set of images. Use the previous and next buttons to change the displayed slide

-

Slide 1: Glauconite. Glauconite forms in shallow, low-oxygen marine environments when there is little or no sedimentation taking place. Glauconite is considered a diagnostic mineral for continental shelf environments.

-

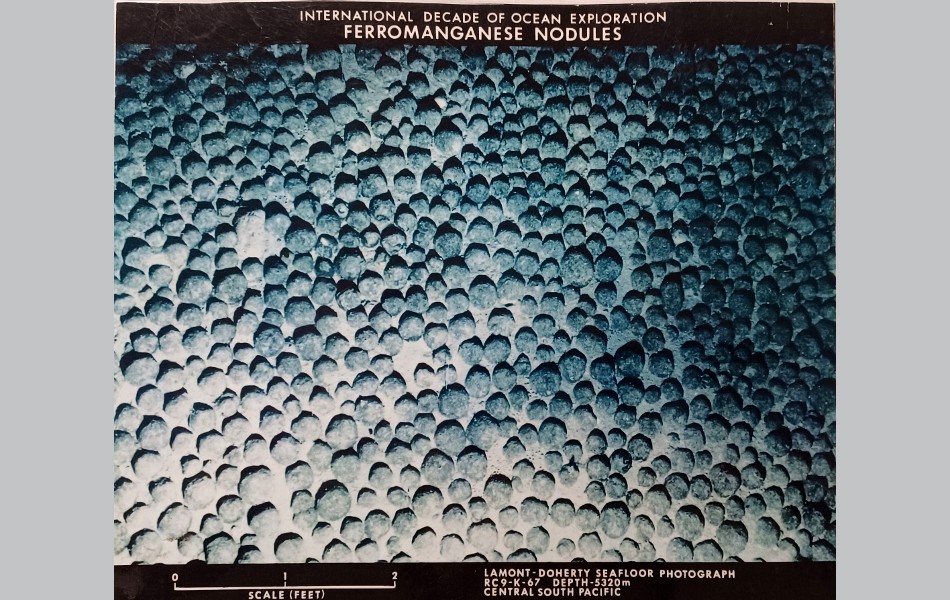

Slide 2: Manganese Nodules. Manganese (Mn) or Polymetallic Nodules are authigenic “rocks” that grow from precipitated metals on the ocean floor. They are formed of concentric layers around a core. We can find micro-nodules in sediment cores and use dredge baskets to gather larger ones.

-

Slide 3: Some parts of the ocean floor (mainly the Pacific and Southern Oceans) are covered in these nodules which can contain small amounts of economically important minerals. However, Mn Nodules are one of the slowest geological phenomena on Earth, growing at an average rate of one centimeter over several million years!

-

Slide 4: This is a split nodule showing the concentric rings of mineral deposition.

-

Slide 5: The core of a Mn Nodule can be almost anything: pieces of coral, pebbles, shells, even shark teeth!

Glauconite. Glauconite forms in shallow, low-oxygen marine environments when there is little or no sedimentation taking place. Glauconite is considered a diagnostic mineral for continental shelf environments.

Manganese Nodules. Manganese (Mn) or Polymetallic Nodules are authigenic “rocks” that grow from precipitated metals on the ocean floor. They are formed of concentric layers around a core. We can find micro-nodules in sediment cores and use dredge baskets to gather larger ones.

Some parts of the ocean floor (mainly the Pacific and Southern Oceans) are covered in these nodules which can contain small amounts of economically important minerals. However, Mn Nodules are one of the slowest geological phenomena on Earth, growing at an average rate of one centimeter over several million years!

This is a split nodule showing the concentric rings of mineral deposition.

The core of a Mn Nodule can be almost anything: pieces of coral, pebbles, shells, even shark teeth!

Other components of sediment cores

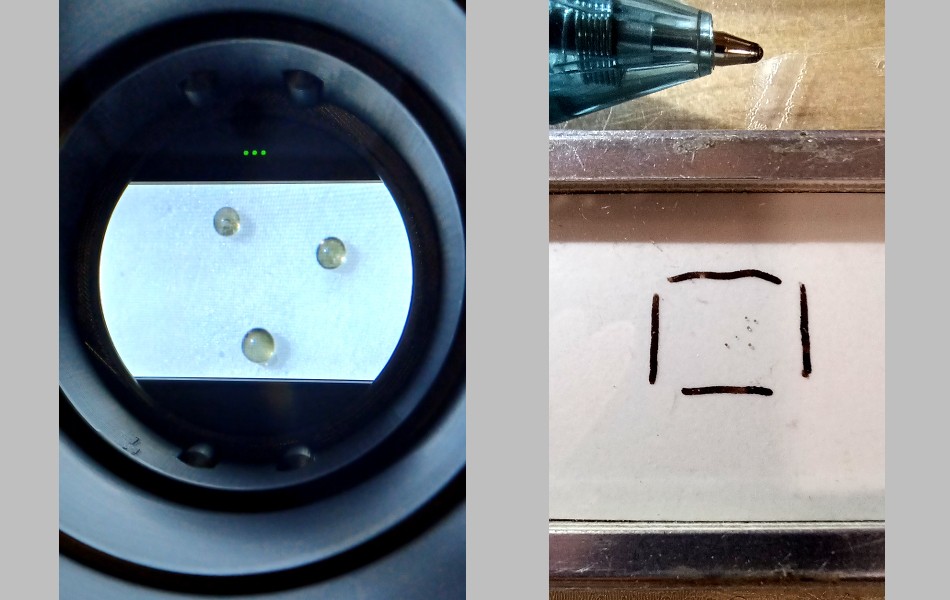

Micro-tektites. Tektites are glass balls that are formed when a meteorite crashes into a terrestrial body (Earth in this case!). The impact melts the dirt and rock beneath the meteorite and ejects this material into the atmosphere. The melted debris cools in spherical shapes while it is flying through the air and, later, falls back to Earth. Below is an image showing what micro-tektites look like with and without a microscope.

Volcanic glass. The composition of lavas is variable and unique to each volcano. Studying volcanic debris in sediment cores can give us clues about eruption histories including how intense an eruption was based on the amount of material and how far from the volcano it is found.